While reading “‘I Do This For Us’: Thinking Through Reciprocity & Researcher-Community Relationships” by Constance M. Haywood and “When the Sound is Frozen: Extracting Climate Data from Inuit Narratives” by Cana Uluak Itchuaquiyaq, the big idea that stood out to me from both of them is that research should do something for the communities that are being studied. This idea feels very intuitive, yet somehow needs to be reiterated again and again. Growing up, writing and researching was taught in a way that encouraged students to keep a certain level of distance from the subject; our jobs were to analyze, intepret, and critique in a wholly neutral way, never inserting ourselves into the research. These authors push back and challenge that sentiment, exploring how this distance hides this power that decides what communities stories are told and for who’s benefit? They also challenge what counts as knowledge; Cana Uluak Itchuaquiyaq shows that by reading Inuit stories as personal archives of data, she’s refusing to acknowledge the dominant idea that only western science and academic writing can be seen as the truth. Both authors show how research is more than just collecting information and data, also about the relationships and communities connected to the numbers.

Obviously, there’s a prominent risk in leaving the actual communities out of the research process. In my area of discipline, literature (and hopefully publishing), stories are the things that shape how we see cultures and history itself. Therefore analyzing a text without recognizing or knowing the community it stems from, there’s the risk of compacting that story into something that’s more relatable for a general audience. Although that might make it easier to teach or get through the stages of publishing, it erases the individuality that gave the story its power in the first place. By including these communities, it creates a deeper and more meaningful understanding, even though it might take away some authority. Collaboration can be hard and messy, but I think that’s a worthy trade, though.

In the areas of literature and publishing, research that includes the communities its working with can look like many things; this might be working with local media that makes an effort to uplift marginalized voices, interviewing and getting personal experiences from readers or authors in said communities, or exploring how online spaces react and reimagine cultural stories. It’s more important to discover how meaning is made within a community than simply taking data for the means of an academic argument.

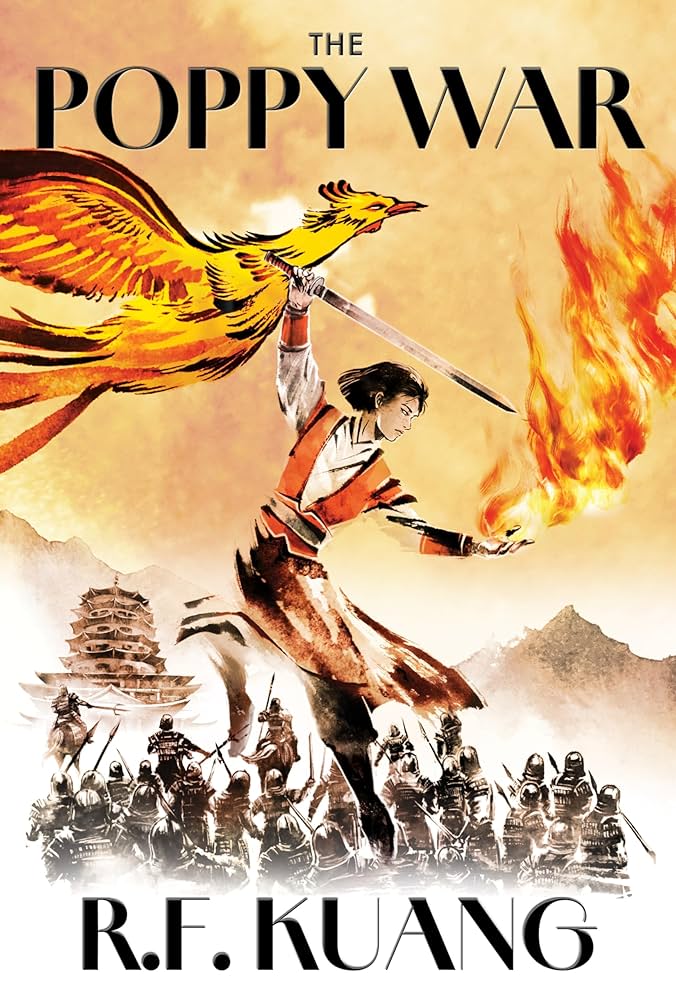

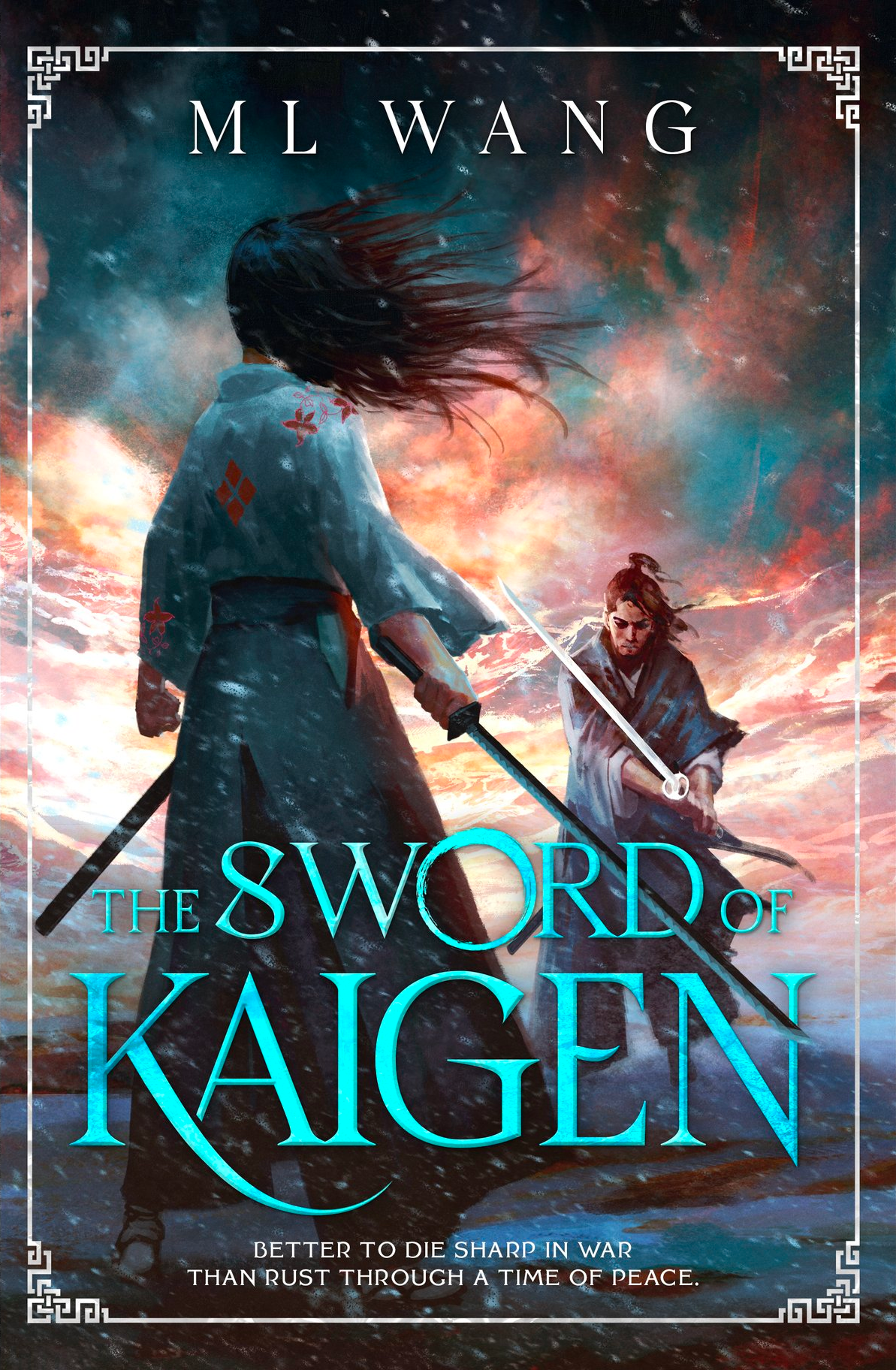

In terms of my own final project in which I’m analyzing R.F. Kuang‘s The Poppy War and M.L. Wang‘s The Sword of Kaigen, I’ve been considering how these novels reimagine ideas of trauma, womanhood, and heroism in a way that challenges the dominant Western perspective. Both of these authors write their stories in discussion with, and against, the larger Western fantasy tradition. The trauma that the main characters endure isn’t romanticized or idealized, but instead explores the various human costs of survival and empire. Looking at my project through the ideas of Haywood and Itchuaquiyaq, I should try not to look at these novels through western frameworks, but explore what these narratives are doing for their own communities. I’m hoping as I dive into my project, it becomes easier to engage with literary analysis as a conversation as opposed to an extraction.

Leave a comment